gridhopping

The algorithm

At the heart of this software is the method I call gridhopping.

We are interested in transforming a shape defined by its signed distance bound into a triangle mesh.

Signed distance bounds are closely related to implicit surfaces of the form F(x, y, z)=0.

In our case, the polygonization volume is an axis-aligned cube centered at the origin.

This cube is partitioned into a rectangular grid with N^3 cells by subividing each of its sides into N intervals of equal size.

If we assume we are not dealing with fractals, only O(N^2) cells asymptotically contain the surface of our shape.

Thus, the only triangles that need to be computed are passing through these cells.

This puts the lower bound on the complexity of the polygonization algorithm.

However, the challenge is to isolate just these O(N^2) cells.

Obviously, the simplest solution, which leads to O(N^3) complexity, is to check each of the O(N^3) cells.

This is too slow for our purposes.

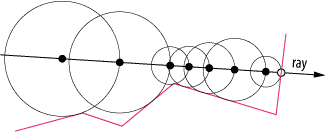

To speed up the polygonization process, we are going to use a variant of ray marching called Sphere tracing, described by John C. Hart. See the paper “Sphere Tracing: A Geometric Method for the Antialiased Ray Tracing of Implicit Surfaces” for more details than are presented here. The basic idea is to define a ray and move along its direction until you find the intersection with the shape or exit the rendering volume. In sphere tracing, the marching step is set to be equal to the (estimated) distance of the current point to the shape. The following figure illustrates this in 2D (the surface is drawn in pink):

This approach greatly speeds up the process of finding the intersection.

In our case, we emit N^2 such rays which are parallel.

All of these rays have their direction vector set in the +z direction: (0, 0, 1).

The centers of the N^2 most distant cells along the -z direstions are used as ray origins.

Once the marching process along the ray hits the surface of the shape, we invoke the polygonization process for the corresponding cell.

However, unlike in the ray marching-based rendering of images, we do not stop the marching process here.

The marching along the ray in continued (starting at the next cell along the +z direction) until the end of the polygonization volume is reached.

Currently, the polygonization of each cell is performed by the Marching cubes algorithm, although other approaches could be used as well

(e.g., Marching tetrahedra).

Complexity analysis

There is experimental and some theoretical evidence that the complexity of the gridhopping method is O(N^2 log(N)).

Preliminary analysis is available here.

Acknowledgements and related work

The development of this software started sometime in the first part of 2019.

Until August, I thought that the gridhopping algorithm was original (invented for this project).

However, it turns our that there is a large literature on how to speed-up marching cubes and some approches are quite similar.

See the paper “A survey of the marching cubes algorithm” by Newman and Li for an overview.

Also, a subsequent analysis of various internet projects revealed that Christopher Olah developed a similar approach around 2011 for his ImplicitCAD.

However, my analysis of its source code on GitHub indicates that its algorithm has N^3 complexity

(although Cristopher discussed improvements that would lead to something like N^2 complexity here ).

I could be wrong though as I am not proficient in Haskel.

Nevertheless, I acknowledge this work and state that gridhopping was developped independently.

Some other projects that inspired this work:

(Note that these use a completely different algorithm under the hood.)

A number of blogs posts, papers and tutorials about ray marching should also be mentioned:

- http://blog.hvidtfeldts.net/index.php/2011/06/distance-estimated-3d-fractals-part-i

- https://www.iquilezles.org/www/articles/distfunctions/distfunctions.htm

- http://jamie-wong.com/2016/07/15/ray-marching-signed-distance-functions

- http://9bitscience.blogspot.com/2013/07/raymarching-distance-fields_14.html

- “GPU Ray Marching of DistanceFields” by L. J. Tomczak

- “SphereTracing: A Geometric Method for the Antialiased Ray Tracing of Implicit Surfaces” by J. C. Hart

- “Enhanced Sphere Tracing” by Keinert et al.

- “Procedural modeling with signeddistance function” by C. L. Diener

Cell polygonization is performed by the Marching cubes algorithm. The implementation closely follows this tutorial.

Rendering is done by three.js.